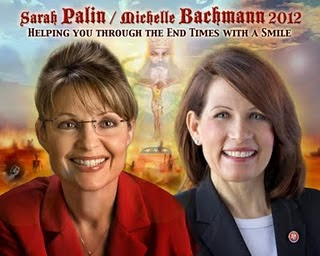

Reading a recent Bachmann profile in The New Yorker My Take: I could have become Michele Bachmann. I could have become Michele Bachmann. Reading a recent Bachmann profile in The New Yorker felt like attending an awkward cocktail party with former best friends whom I now stalk on the internet but haven’t spoken to in years.

The story describes Bachmann’s influences-including figures like Francis Schaeffer and David Noebel, who most Americans have never heard of but who are superstars in conservative Christian circles-and I found them all familiar faces from my childhood as a culture warrior. Bachmann wins Iowa straw poll: These are people Bachmann admires and people I once admired, too. Bachmann has protested at abortion clinics. I was attending abortion protests when I was still too young to hold a sign or even walk.

Bachmann began trying to combat the influence of liberals and secular humanists after encountering Francis Schaeffer’s 1970s’-era video series "How Should We Then Live," a plea to reclaim Western institutions from the corruption of secularism.

I watched the series with my parents as a child: Bachmann served on the board of directors for Summit Ministries, which sponsors conferences and institutes aimed at equipping evangelicals with a Christian worldview. I attended Summit Ministries’ Student Worldview Conference as a 15-year-old.

On the first night of the program, I sat rapt through a talk about a Christian dress code that spelled out the width of the shoulder straps I was permitted to wear, which was not a problem for me because I had brought only oversized Republican campaign t-shirts and shorts that were styled for a 35-year-old mom.

They gave us a handy worldview chart that had a vertical column for every area of life - economics, politics, pyschology, law - and a horizontal column that showed how Muslims, humanists, Marxists and New-Agers were wrong on every count.

The program’s leaders said that the Bible calls for limited government, and that God’s law and nature’s law were good foundations for a legal system. The Christian believes the free enterprise system to be more compatible with his worldview than other economic systems, I learned.

Bachmann began trying to combat the influence of liberals and secular humanists after encountering Francis Schaeffer’s 1970s’-era video series "How Should We Then Live," a plea to reclaim Western institutions from the corruption of secularism.

I watched the series with my parents as a child: Bachmann served on the board of directors for Summit Ministries, which sponsors conferences and institutes aimed at equipping evangelicals with a Christian worldview. I attended Summit Ministries’ Student Worldview Conference as a 15-year-old.

On the first night of the program, I sat rapt through a talk about a Christian dress code that spelled out the width of the shoulder straps I was permitted to wear, which was not a problem for me because I had brought only oversized Republican campaign t-shirts and shorts that were styled for a 35-year-old mom.

They gave us a handy worldview chart that had a vertical column for every area of life - economics, politics, pyschology, law - and a horizontal column that showed how Muslims, humanists, Marxists and New-Agers were wrong on every count.

The program’s leaders said that the Bible calls for limited government, and that God’s law and nature’s law were good foundations for a legal system. The Christian believes the free enterprise system to be more compatible with his worldview than other economic systems, I learned.

No comments:

Post a Comment